Enterprise Knowledge Has a Face

Corporate portals centralize enterprise information access in a graphically rich, application-independent interface that mirrors "knowledge- centric" workflow

By Hadley Reynolds and Tom Koulopoulos

“Portal” is the term du jour, and virtually everyone using Internet technologies is integrating portal visits into their online experience. No single task involves a single information resource; even the simplest knowledge work involves coordinating multiple data sources, processes, and people. That’s where portals come in, providing a single point of integration and navigation through the enterprise. Exploring warp-speed, Internet portal development will show you how you can capture process knowledge and make it an asset for your organization.

Wall Street’s year-long mania with Internet shares has unearthed scores of new company names and business plans, but Internet portal companies are receiving the most attention. In addition to Yahoo!, Lycos, Infoseek, and Excite, there are also the broad-based players such as Netscape, AOL, AltaVista, and—coming soon—Microsoft. It may seem incongruous that the hottest names on the Web are pointing the way to the next phase of information management for the wired corporation, particularly because site content is of little or no fundamental business value. How have portals evolved into organizational value providers?

The Brief History of Portal Development

Three years ago, what we now call portals were referred to as “search engines.” Based on simple Boolean search technology applied to HTML documents, the search engine’s initial value proposition was simple: No one could hope to locate anything in the vast Web environment through “conventional” means, such as volume and directory specifications or file names. Search engines, however, offered document content with full text indexes—a great leap forward and a chance to take advantage of the new hyperlinking capabilities built into Web protocols.

Initially, the search engines assumed that users could navigate raw associative links. But it soon became evident that giving people a complicated search command language to find simple weather, travel, and sports information was not going to be acceptable to users. In order to address user frustration and reduce the average “seek time” to find relevant information, the search sites added the function of categorization—filtering popular sites and documents into preconfigured groups according to content meaning (sports, news, and finance, for example). “Navigation sites” became the term used to describe the new functions available at Excite, Infoseek, Yahoo!, and Lycos.

The latest development wave has ushered in the terminology of Internet “portals.” These sites now not only provide search functionality and a library of categorized content, but have expanded to offer such additional features as access to “communities of interest” (Yahoo! Financial’s threaded discussions, for example); realtime chat options; content personalization by user specification (My Excite); and direct access to specialized functions (shopping networks, auctions, and online trading sites).

At the root of all this change is the constantly articulated proposition that you should have a single access point from which to make connections for all your Web information needs—news, shopping, or content browsing. Web “consumers” have been unwittingly teaching the corporate world about this need, but do internal knowledge workers have different information requirements?

Note the basic progression in the Web portal story: A search leads to navigation (categorization), which moves on to personalization and expanded functions into other areas of the information and commerce worlds. Even if we wouldn’t want to relive the Internet experience inside the corporate firewall, doesn’t this progression tell us something about the ways we can adopt the principles in the business world?

The Portal Mission

Public portals and the emerging corporate portal are divergent branches in the computing evolution. They exist to fulfill different purposes for different user groups. The central difference is in the underlying mission of the portal itself: On the Internet, a portal site’s business model is based on attracting a portion of the corporate advertising budgets that might otherwise be allocated to other media advertising (print, television, and radio).

The purpose of the public portal is to attract large numbers of repeat visitors, building online audiences with compelling demographics — the inclination to buy what portal advertisers have to sell. Since defining themselves as “new media,” public portals have essentially settled into a unidirectional relationship with their viewers.

On the business desktop, however, the portal takes on an entirely different character. Its purpose is to expose and deliver business-specific information—in context—to help today’s computer-based worker stay ahead of the competition. Being competitive requires a bidirectional model that can support knowledge workers’ increasingly sensitive needs for interactive information-management tools.

As we rapidly deploy intranets, we use new capabilities that identify, capture, store, retrieve, and distribute vast amounts of information from multiple internal and external sources at individual, team, or function levels. They’re pushing the envelope of legacy computing infrastructures as well as challenging the assumptions of current information processing models, resulting in a possible shift from information systems as a group of isolated programs addressing discrete disciplines toward a ubiquitous information environment.

At press time, this shift is precipitating a gradual transformation of the information industry. The shift has implications for major industry players’ business models—particularly Microsoft. But the core dynamic driving the rise of the corporate portal is that our expectations for computer use are changing dramatically from acquiescence in a program-by-program, task-isolated environment to enthusiasm for an integrated environment providing information access, delivery, and work support across organizational dimensions. We’ve become acutely aware that the familiar applications-based desktops create islands of automation. They separate and segregate functions that are intuitively part of the same process; it’s like using a different type of phone for every state you want to call. Computer users have suffered with this absurd state of affairs in resigned silence, at least until the advent of the Web and the intranet.

User-Centric Focus

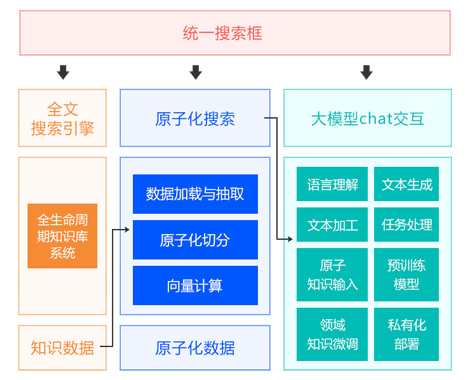

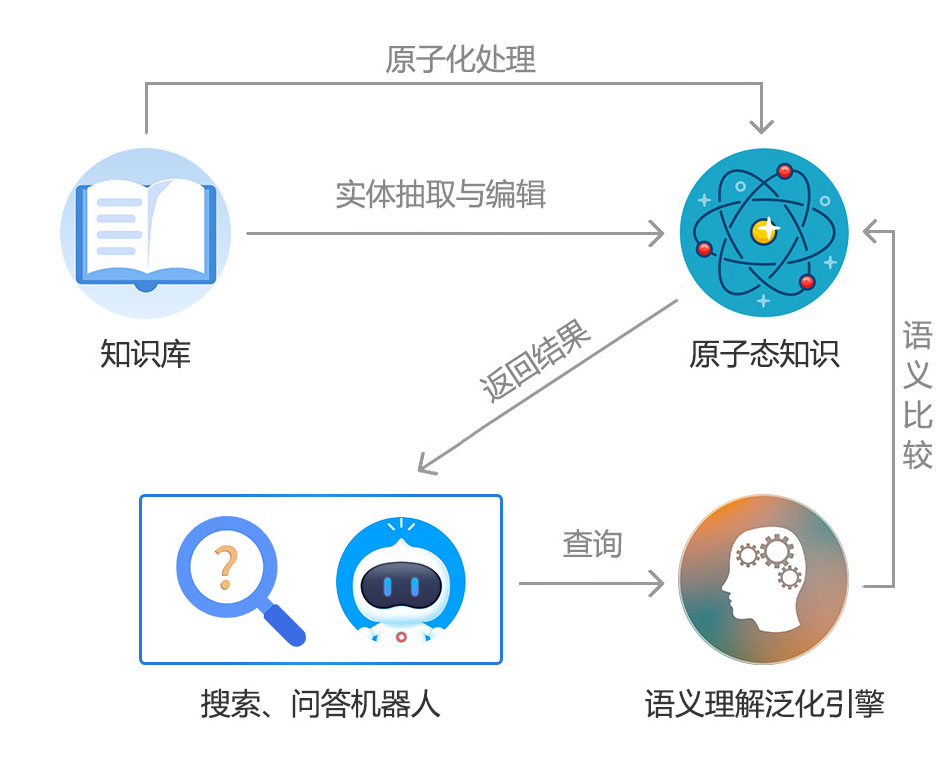

Most organizations today are poorly positioned to take advantage of the recent proliferation of rich internal corporate information sources resulting from rapid intranet, enterprise application, and electronic business development. The problems arise from two fundamental aspects: First, there’s been an explosion in the quantity of key business information captured (imprisoned) in electronic documents. Organizations are losing their grip on information as they transition into new systems and process upgrades. Second, the speed with which information quantity and content types is growing means that you need a rigorous internal discipline to expose and integrate enterprise knowledge sources. (See Figure 1.)

FIGURE 1 Knowledge sources for integration.

Disparate corporate information is difficult to reconcile and organize across an enterprise. The corporate portal’s most compelling promise is that it offers a unique integration capacity that takes advantage of corporate information’s inherent purpose and structure. A portal crafted around these naturally occurring centers of action and interest can yield a degree of relevancy that’s nonexistent in broad-based Internet data sources.

Corporate and Internet portals’ strength lies in their ability to organize information in the absence of a centralized, predetermined information ontology. In other words, individuals share the responsibility for classifying business-critical information. Publishing and other information-sharing activities generate a rich content environment at the corporate portal level without requiring a comprehensive overview. This new environment creates that single point of access for the increasingly “knowledge-centric” patterns of today’s work world. Corporate portal developers focus on a user-centric information system that provides access to working information within one interface — a graphically rich, application-independent interface that will ultimately make the contemporary, two-dimensional, window-based metaphors look as obsolete as the IBM 3270 terminal interface.

You can’t underestimate the contribution of “messy desk” windowing systems in our computing environment’s development. Many industry players credit the mid-1980s Macintosh windowing environment for letting users cut and paste text and data between applications for the first time. But does having 20 windows open on your desktop let you work more effectively? You don’t have obvious bonds (links) between the processes underlying the information and your context of information use. In other words, a messy desk interface segregates applications’ information content and doesn’t provide an integrating display adjusted (contextualized) to the user’s work situation. Can someone looking over your shoulder appreciate what process you’re involved in by glancing at your desktop? Is the desktop reflective? Is it obvious what process you’re working in when you look at your desktop? That’s unlikely. In fact, early Mac windowing advances (copied and popularized in Microsoft Windows) actually obscured the early Mac’s more fundamental advance — Hypercard, the hypermedia development environment, which opened the promise of information integration now being fulfilled on the Web.

Today, it’s not outrageous to predict that applications will fade within a decade. Word processing, spreadsheets, and databases will become part of a single integrated business environment in which corporate portals will play a major role in navigating and delivering personalized information tools and content. Users will view proprietary systems such as Windows as a relic of a former, highly restrictive, and unacceptably unproductive era. Windows is the last technology from the age of information scarcity; it was never designed to accommodate the age of information abundance.

What Portals Can Do for You

How will this transformation take place? The emergence of the corporate portal is the initial step in providing a working platform for this age of information abundance. Even in their earliest stages, corporate portal applications provided three key benefits: structured access to information across large, multiple, and disparate enterprise information systems; a highly personalized view of the enterprise for each user; and a bridge for the discontinuity of today’s fast companies experiencing mergers, downsizing, or worker “free agency.”

Today, portals feature even more dynamic capabilities that give them an ambitious role in the organization. They can:

?Automate identification and distribute relevant content

?Go beyond search and retrieval to provide content sensitivity

?Interact intelligently with users, letting them profile, filter, and categorize support to manage information overload

?Expose the actual distributed enterprise information taxonomy. This task is impossible to accomplish through centralized legislation. Unlike today’s applications that automate discrete work elements, corporate portals define a new information aggregation level that radically changes the character of the working desktop.

Contrary to the public Internet, a corporate portal provides an information structure that exists in a company’s information taxonomy as it reveals itself in use. You can categorize all information according to at least one of the following organizational forms that also correspond to the three layers in an organization:

Physical—The actual information location or ownership, which you can’t centralize and is usually cross enterprise. The physical layer in a company is the infrastructure supporting the processes. Example: document management systems.

Prescribed—The formal categorization based on regulatory, policy, or historical mandate. This “process” layer is the organization itself; it involves defining the process according to managers and executives—frequently outdated sources. Example: database.

Practical—The actual information needed without regard to its location or prescribed use. This “people” layer is concerned with the way coworkers interact, as well as how they work around the obstacles the other two layers present. Workers may be afraid to explicitly go against corporate policy to get things done or fear a layoff if they reveal what they actually do to get their work accomplished. This layer is more spontaneous and rarely documented, mostly because employees appreciate their job security. Example: an email system.

Corporate information content already includes these structural elements; there’s not utter chaos. This “context sensitivity” is critical in corporate portal development, because the sensitivity helps envision the alternatives it creates in a three-dimensional matrix.

Using all three of the systems in any single operation or process results in a patchwork, manual enterprise view. You leave critical information out of the picture, and relevant connections are virtually nonexistent. But using the three systems in a corporate portal gives you a cohesive enterprise view. The single access point offers a superior alternative for the middle office worker forced to coordinate these information streams manually.

We define the middle office by the knowledge workers’ roles positioned between front- and back-office systems. Although both systems have reached a stage of equilibrium and parity across most industries (thanks to extensive enterprise applications deployment for structured transactions), middle office workers live in a dynamic and unpredictable world. Their success lies in their ability to coordinate myriad information feeds, personal connections, and process interactions. Rarely externalized tacit knowledge determines workers’ ability to navigate this maze effectively and quickly. But the middle office is the point where you most often realize competitive differentiation—where you design products, support and retain customers, minimize risk, and maximize profit.

What the corporate portal introduces to the middle office is a contextualized echo of the Internet portal sites—only this time with bite. The corporate site’s defining feature is that it embodies the work context, something a public site will never do. The same progression we’ve seen on the Web is now underway inside the organization: from comprehensive searching across multiple sites (that is, all corporate applications and information sources) to navigating and categorizing material.

Beyond the Portal’s Doors

We can only speculate about how the information industry landscape will look in 10 years, when corporate portals become a standard part of the enterprise. We won’t refer to “portals,” because the range of functionality available from information appliances will have long since left the image of “gateway” behind. Each organization will have moved its business model fully into electronic mode, and the last remaining pieces of legacy software from the era of applications will be phased out. Knowledge workers won’t complain about application isolation and the contradiction between computer use and productivity.

One potential irony is that the portal is likely to become a heated battleground for intellectual property issues. Individuals who become accustomed to this new technology are bound to realize the incredible value they can develop—not only for the enterprise but to their own careers, their own free agency, and perhaps even their legacy. After all, if information is truly the greatest asset, the value generated and realized through the corporate portal becomes a matter of personal—not just organizational—wealth.

Hadley Reynolds directs research programs at The Delphi Group. You can reach him at hr@delphigroup.com.

Tom Koulopoulos is the founder and president of The Delphi Group, an international research and consulting organization focused on the business application of unstructured information management technologies. Tom has written several books, including Smart Companies, Smart Tools (John Wiley & Sons, 1997). You can reach him at tk@delphigroup.com.

2017-03-18 10:30

2017-03-18 10:30